One of the first things you think of when considering learning languages or studying how they work is the aspect of how they sound.

In the same way that a person could learn to read a language without speaking it by recognizing the different written symbols the language uses and how each makes up a meaningful part of a word, so too do speech and pronunciation provide a similar base from which a person can hear and interpret the meaning of spoken language. Orthography, or the way a language is written, is simply the bridge between the sounds we make and the way we read.

Anyways, sound is important. You can’t just throw random utterances around with a picture of what you want to convey in your mind and expect it to be correctly interpreted. There are rules that certain languages adhere to in the way that meaning—through these correct sounds and sound structures—can be interpreted. The study of these rules is called phonology, while the study of the sounds themselves and how they’re made is called phonetics.

Phonetics is the smallest level of the study of languages. It is the sounds available in a language that form the rules for the way in which they are put together, which then touches the smallest level of the study of meaning in language (which is called morphology), and from there it just grows to bigger levels.

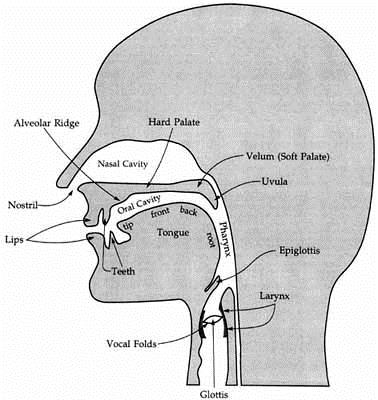

This field of study is also the closest linguists have to natural science, being largely centered in biology. This is because they need to understand how sound is made (through different parts of the mouth and throat), how it is heard (through the biology of the human ear), and how it is analyzed in the brain.

Linguists use the biological areas in the following chart to describe the sounds they hear, along with the type of physical movement made to produce the sound in that spot:

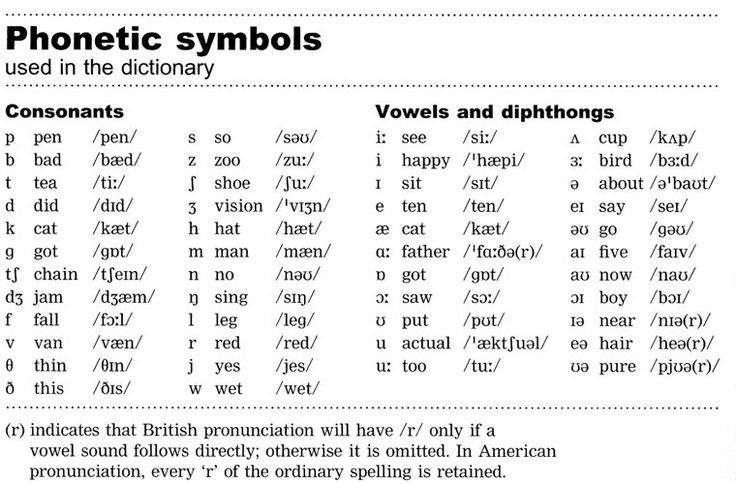

There are over one hundred different sounds recorded in human speech (and some alterations to these sounds, such as aspiration and intonation), all of which need to be recorded in order to discuss phonetic science. Thus, since 1888 linguists (among other fields associated with speech: pathologists, singers and actors, lexicographers, and translators, to name a few) have used a system for expressing them on paper.

We can’t simply use the letters in our alphabet to talk about these sounds. Even within English the letter “a” is used in a few different ways to produce different vowel sounds (for example, compare the “a” in “cat” to “mate” to “all”). These differences also exist between languages, as each has its own way of writing the sounds it features, and some don’t even use the same Latin alphabet we do! We thus needed a way of talking about and comparing these sounds outside of all of that.

As a result, the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) was created! With 107 letters, 52 diacritics, and four prosodic marks, the IPA is a very helpful tool to any whose job it is to work with human noises, or even for those who want to learn another language, as it puts all of the sounds of that language on a phonetically legible level such that the learner does not need intense contact with native speakers or audio in order to make the sounds of the language themselves.

Here is a small sample of the IPA in an English context. They’re not too hard to learn because many of the letters used are Latin, as it was westerners who created IPA.

Phonology is very similar to phonetics. Where the latter deals only with the sounds of a language, phonology is the study of how those sounds fit together and change depending on their place in the sentence. As a result it still has a basis in biology, because certain sounds made separately do not sound quite that same way when made consecutively because of the physical aspect of the way they are made in a person’s mouth (for example hold your hand up in front of your mouth and say the words “pot” and “spot,” feeling the air, called “aspiration,” from the former and none from the latter, representing variations of the same sound).

These sounds, which we as laymen would believe sound the same, are actually the basis for linguistic changes in pronunciation. An example of this would be the “sh” sound in “sugar,” which always sends English learners through a loop. These sounds are represented by phonemes, which are the mental representation of a sound, and when we have a deviation created by a certain order of sounds, that is called an allophone of the phoneme in our mind.

The studies of phonetics and phonology greatly overlap but they do have their foci. And though they are not technically the smallest level of linguistic meaning, they do provide the foundation under which that meaning becomes overlaid. The next progression up the ladder, then, is morphology!